An atypical presentation of polymorphic eruption in early pregnancy in a 40-year-old female: case in images

SPMC J Health Care Serv. 2023;9(2):2 ARK: https://n2t.net/ark:/76951/jhcs48xse6

1Department of Dermatology, Southern Philippines Medical Center, JP Laurel Ave, Davao City, Philippines

Correspondence Andrea Isabel Contreras, andiscontreras@gmail.com

Received 12 May 2022

Accepted 5 October 2023

Cite as Contreras AI, Belisario MP. An atypical presentation of polymorphic eruption in early pregnancy in a 40-year-old female: case in images. SPMC J Health Care Serv. 2023;9(2):2. https://n2t.net/ark:/76951/jhcs48xse6

|

|

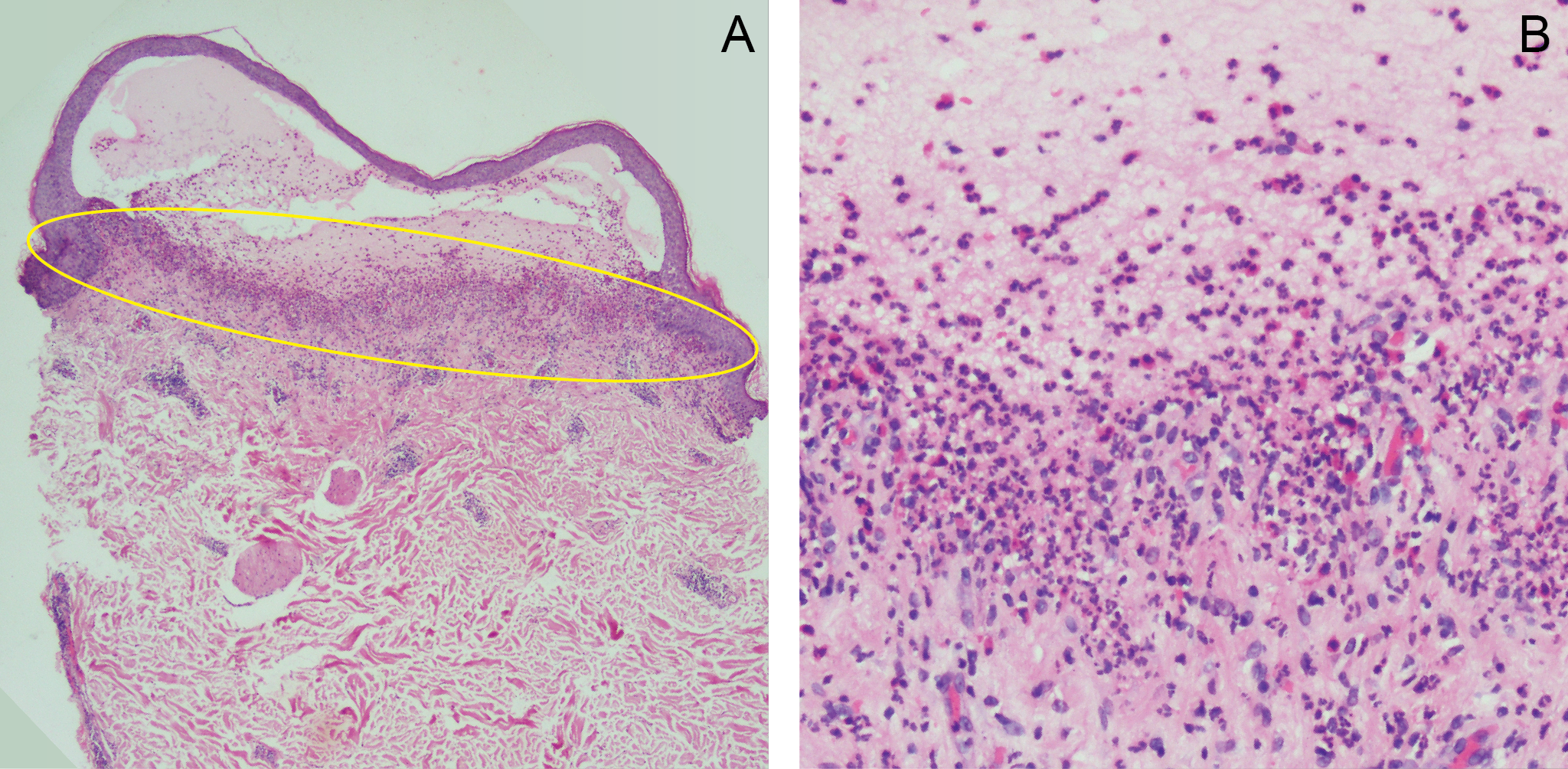

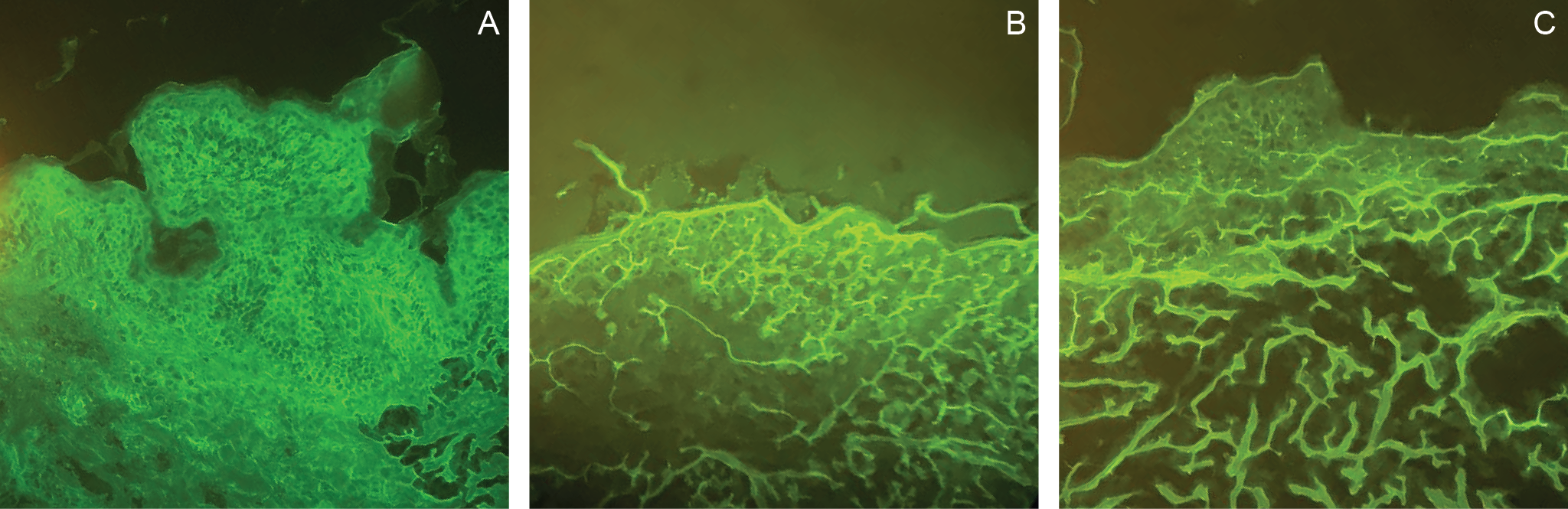

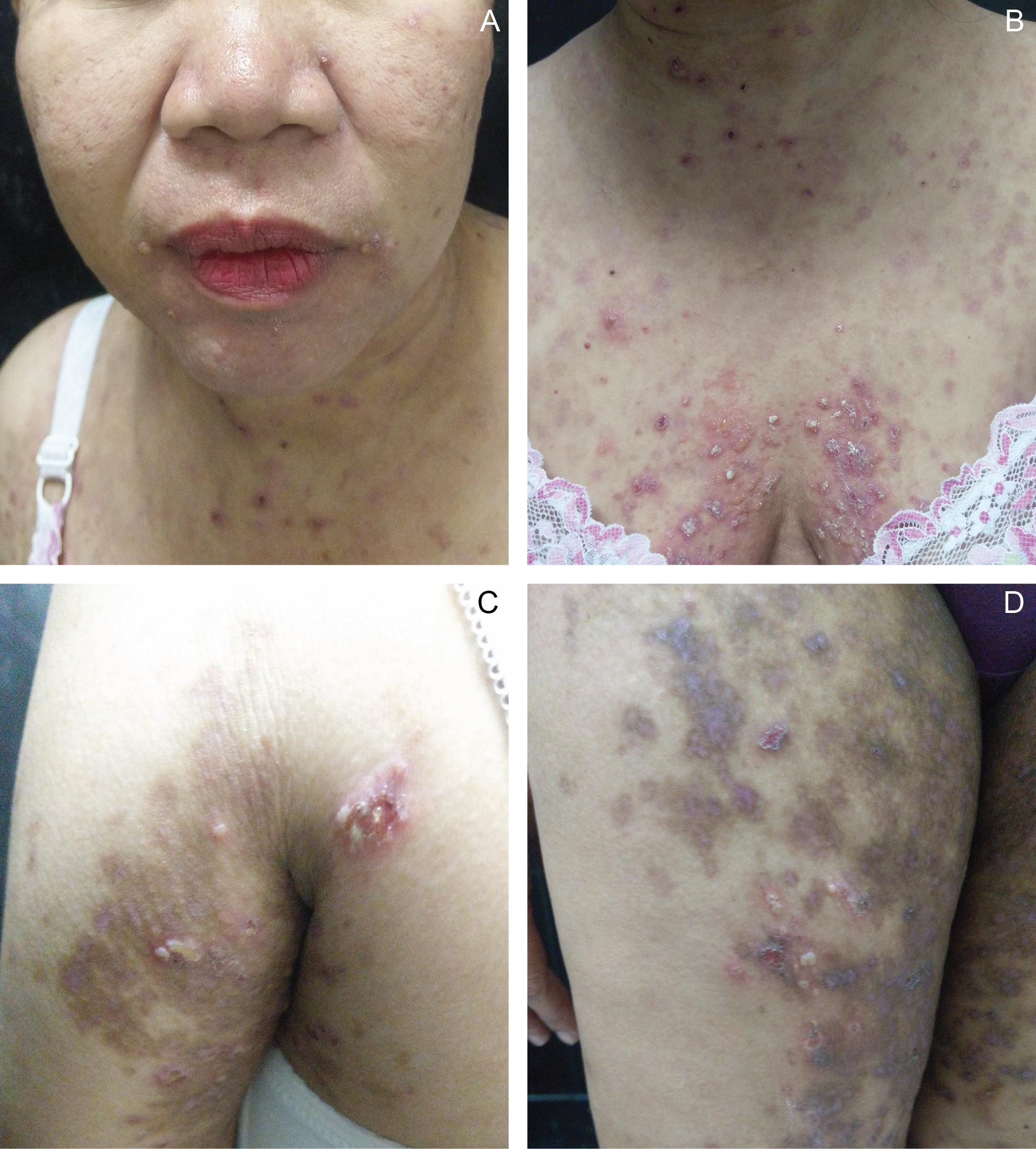

Figure 1 Multiple tense vesicles and erythematous urticarial plaques on the face (A), chest (B), and upper (C) and lower extremities (D) noted at 26 weeks postpartum. |

Contributors

AIC and MPB contributed to the diagnostic and therapeutic care of the patient in this report. All of them acquired relevant patient data, and searched for and reviewed relevant medical literature used in this report. AIC wrote the original draft, performed the subsequent revisions. All approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of this report.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Jen-Christina Lourdes Segovia of the Department of Dermatology in Southern Philippines Medical Center (DD-SPMC) for her help in the management of the patient, and Dr Nadra Magtulis, also from the DD-SPMC, for her assistance in creating this case report.

Patient consent

Obtained

Article source

Submitted

Peer review

External

Competing interests

None declared

Access and license

This is an Open Access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which allows others to share and adapt the work, provided that derivative works bear appropriate citation to this original work and are not used for commercial purposes. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

References

1. Brandão P, Portela-Carvalho AS, Melo A, Leite I. Post-partum Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Cases Rev. 2018; 5:139.

2. Pritzier EC, Mikkelsen CS. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy developing postpartum: 2 case reports. Dermatol Reports. 2012 Jun 6;4(1):e7.

3. Pierson JC. Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy. 2020 Feb 21 [cited 2023 Oct 13]. In: Medscape. New York: Medscape. c1994-2023. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1123725-overview?form=fpf.

4. Oakley A. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. 2017 Sep [cited 2023 Oct 13]. In: DermNet. New Zealand: New Zealand. c2023. Available from: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/polymorphic-eruption-of-pregnancy.

5. Pomeranz MK. Dermatoses of pregnancy. 2023 Aug 23 [cited 2023 Oct 13]. In: UpToDate. Netherlands: Wolter Kulwer NV. c2023. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatoses-of-pregnancy.

6. Mehedintu C, Isopescu F, Ionescu OM, Petca A, Bratila E, Cirstoiu MM, et al. Diagnostic Pitfall in Atypical Febrile Presentation in a Patient with a Pregnancy-Specific Dermatosis-Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022 Jun 25;58(7):847.

7. Calinescu A, Popescu R, Popescu CM, Hodorogea A, Brinzea A, Zeiler L, et al. Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy with Postpartum Onset: A Case Report. EMJ Dermatol. 2018;6(1):99-100.

8. Studdiford JS, George N, Trayes K. Pruritic Rash in Pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Apr 1;95(7):453-454.

9. Kwon EJ, Ntiamoah P, Shulman KJ. The utility of C4d immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue in the distinction of polymorphic eruption of pregnancy from pemphigoid gestationis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013 Dec;35(8):787-91.

Warning: mysqli_select_db() expects exactly 2 parameters, 1 given in /home/qrjicuku/public_html/V9N2Galley/Contreras/Contreras.php on line 385

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License that allows others to share the work for non-commercial purposes with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional, non-commercial contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors grant the journal permission to rewrite, edit, modify, store and/or publish the submission in any medium or format a version or abstract forming part thereof, all associated supplemental materials, and subsequent errata, if necessary, in a publicly available publication or database.

- Authors warrant that the submission is original with the authors and does not infringe or transfer any copyright or violate any other right of any third parties.