Metachronous occurrence of anal melanoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma in a 72-year-old female: case in images

SPMC J Health Care Serv. 2020;6(2):8 ARK: https://n2t.net/ark:/76951/jhcs6jq5t3

Stephen Matthew B Santos,1 Stephanie Salvoro,1 Maynard Hernal,1 Orlando F Basilio1

1Department of General Surgery, Southern Philippines Medical Center, JP Laurel Ave, Davao City, Philippines

Correspondence Stephen Matthew B Santos, stephensantos4@gmail.com

Received 18 December 2019

Accepted 23 December 2020

Cite as Santos SMB, Salvoro S, Hernal M, Basilio OF. Metachronous occurrence of anal melanoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma in a 72-year-old female: case in images. SPMC J Health Care Serv. 2020;6(2):8. https://n2t.net/ark:/76951/jhcs6jq5t3

Anal melanoma is a rare melanocytic malignancy, which roughly comprises 2% of all anorectal malignancies.

1 2 The anal area is the most common site for primary gastrointestinal melanomas.

2 Patients with anal melanomas commonly complain of bleeding, anal pain and mass, tenesmus, and changes in bowel habits. In cases with metastases, symptoms such as weight loss, anemia, fatigue and bowel obstruction could be present.

2 Risk factors of anal melanoma include old age, multiple sexual partners, anal sex, smoking, history of other malignancies (i.e., cervical, vulvar, or vaginal cancer), activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase c-Kit, and family history of malignancies.

3 4 The diagnosis of anal melanoma is established through biopsy—usually done with colonoscopy—and immunological staining.

5 HMB-45 is the immunological stain commonly used for the detection of both primary and metastatic melanomas.

6 Endoscopic ultrasonography also helps to characterize lesions and assess the depth of infiltration.

7

Surgery remains to be the cornerstone of the management of anal melanomas.

8 Because of the rarity of the malignancy, there is no consensus on the better surgical approach, which could either be abdominoperineal resection (APR) or wide local excision (WLE), with or without adjuvant radiotherapy.

9 Currently, it is unclear whether patients who undergo APR—rather than WLE—will have better prognosis.

1 Chemotherapy or radiotherapy can be used for advanced disease.

1 The prognosis of anal melanomas remains poor, with less than 20% survival rate among patients with the condition five years after diagnosis.

1 10 11

Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is the most common thyroid cancer which accounts for 80-85% of all thyroid cancer cases.

12 13 14 A risk factor for PTC is exposure to low or moderate doses of ionizing radiation.

15 16 Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) is highly accurate in diagnosing PTC—with a sensitivity of nearly 80% and a specificity of nearly 100%

17—and is more efficient when guided by ultrasound.

13 PTC is easily treatable and is associated with a good prognosis.

12 15 Lobectomy is considered an option for patients with unifocal tumors not greater than 4 cm in size and with no extra-thyroidal extensions or metastases to surrounding lymph nodes.

18 For patients with tumors greater than 4 cm or with gross extra-thyroidal extensions or lymph node metastases, near total or total thyroidectomy and gross removal of all primary tumors is considered.

12 Radioactive iodine therapy and lifelong thyroid hormone therapy usually follows thyroidectomy.

19 20

Multiple primary malignancies (MPM) may involve a single anatomical organ or multiple separate organs.

21 22 According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, MPMs arising in different sites, are divided into: synchronous cancers, which occur at the same time or within six months of the first primary cancer; and metachronous cancers, which occur in sequence and greater than six months apart.

23 24 Patients with first primary thyroid cancers have a 30% increased risk of developing a second primary cancer.

25 26 Early diagnosis of a second malignancy and its immediate management improve the patients’ prognosis.

27

We report the case of a 72-year-old female who came in due to a 7-month history of bleeding from a huge anal mass, with a 4-year history of an untreated anterior neck mass on the background. We successfully resected the anal mass, but the patient never consented to a definitive treatment for the neck mass.

A 72-year-old female was admitted to our service (General Surgery) due to rectal bleeding. The bleeding started seven months prior to admission. A consultation with a physician in another hospital established a mass, about 2 x 2 cm in size, on the anal area to be the cause of the bleeding. The histopathology of an incision biopsy done on the mass reported stratified squamous epithelium overlying densely packed atypical cells with round to ovoid hyperchromatic and prominent nuclei and scanty to moderate amounts of cytoplasm, and some atypical cells around vascular channels一findings, which are consistent with malignant round cell tumor. An immunohistochemical analysis performed on the specimen revealed the presence of HMB-45 antibody, supporting the diagnosis of malignant melanoma. The patient was advised further work-up and eventual surgery. The patient decided not to pursue the treatment plan because she was able to tolerate the anal mass, which was initially painless and would only bleed intermittently in scant amounts. However, the mass grew gradually in size and, over a few months, the patient noted progressing discomfort when sitting or defecating.

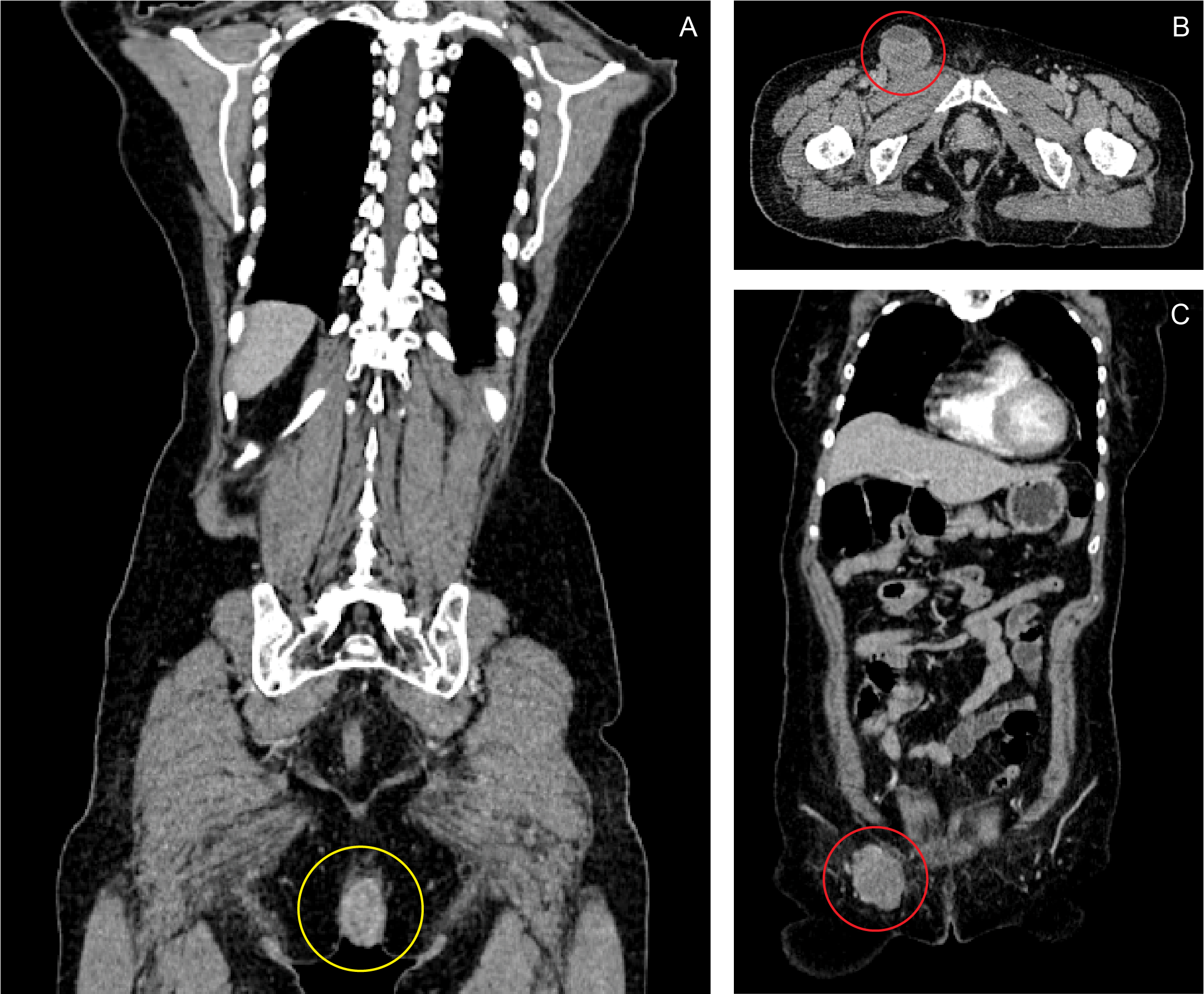

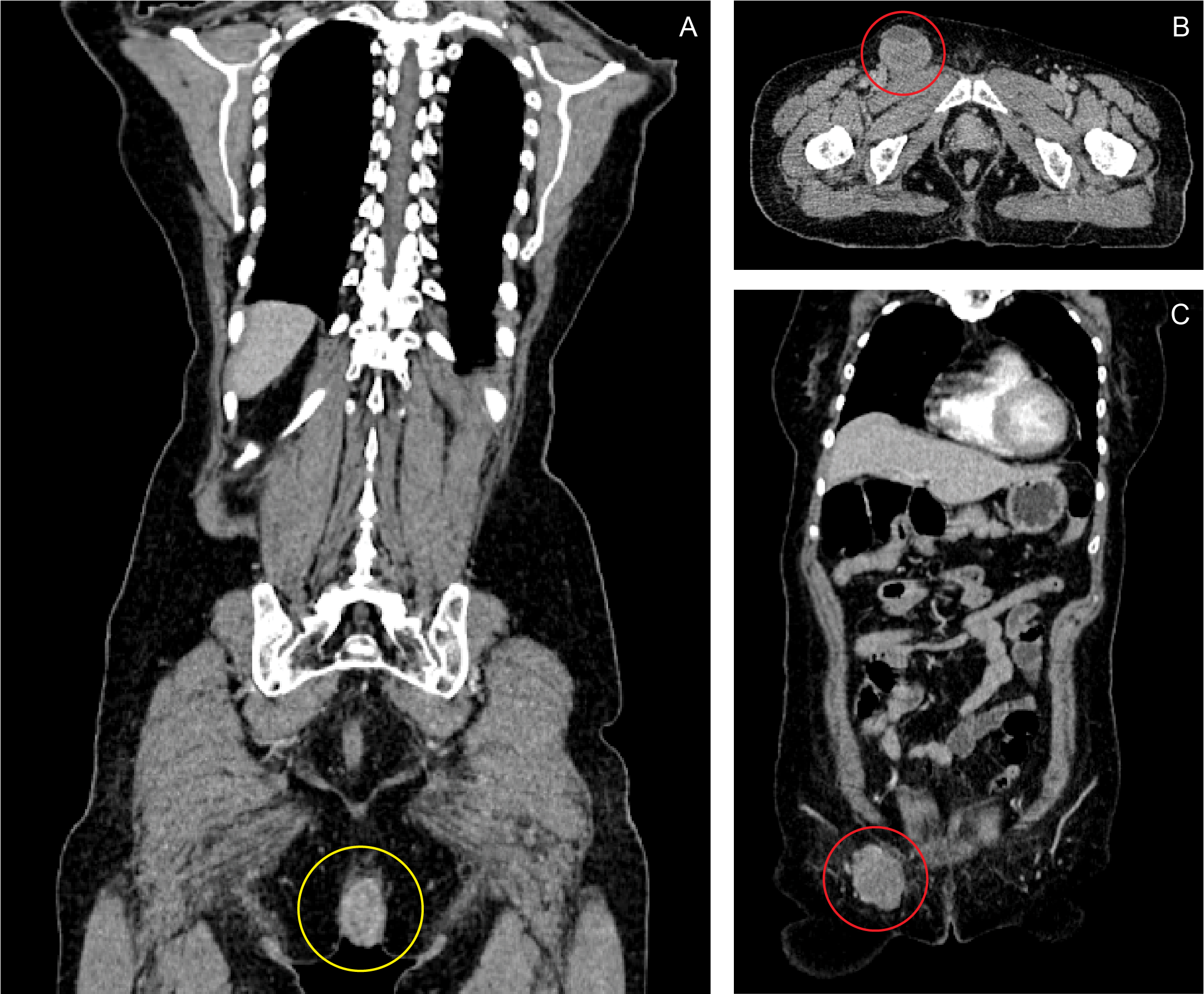

A month prior to this admission, she went back to her first physician because the bleeding episodes had become more frequent, and the anal mass already measured around 6 x 7 x 6 cm by this time. The patient decided to pursue treatment in our hospital. A colonoscopy was done, which demonstrated that the base of the pedunculated anal mass was located at the right posterolateral aspect of the anal canal, extending from the anal verge and reaching up to the dentate line, with a base measuring 2 cm in diameter. No masses or other lesions were found from the cecum down to the rectum. A CT scan of the whole abdomen with contrast showed a fairly defined heterogeneously enhancing mass, measuring 5.40 x 3.14 x 5.81 cm in size and infiltrating the puborectalis muscle, anal sphincter and perineal muscles. A second, well-defined, lobulated, enhancing, hypodense mass measuring 5.29 x 4.58 x 4.33 cm in size was also noted at the right inguinal area. (Figure 1) The characteristics of both masses were consistent with an anal malignancy with perianal muscle infiltration and inguinal lymph node metastasis.

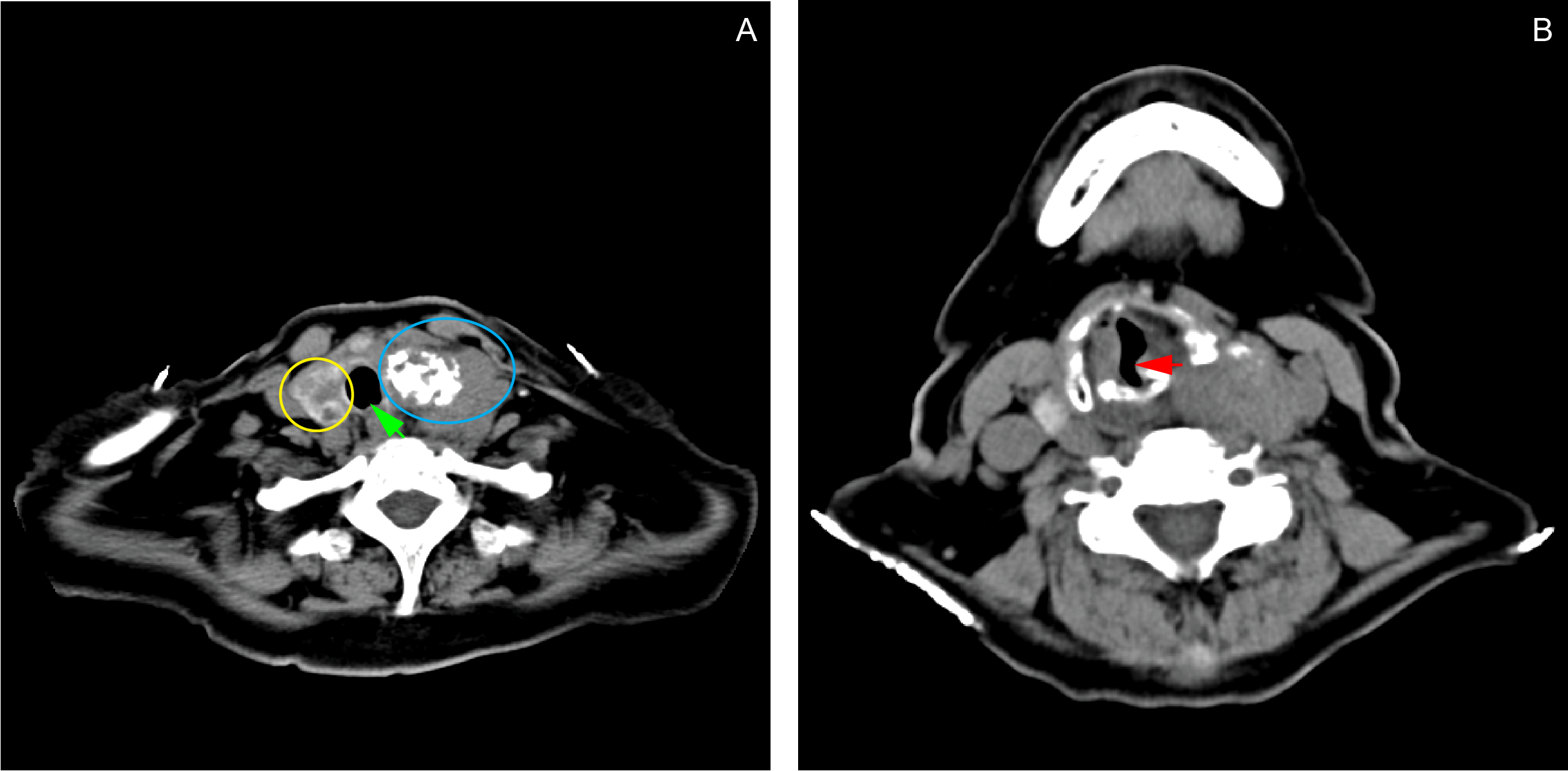

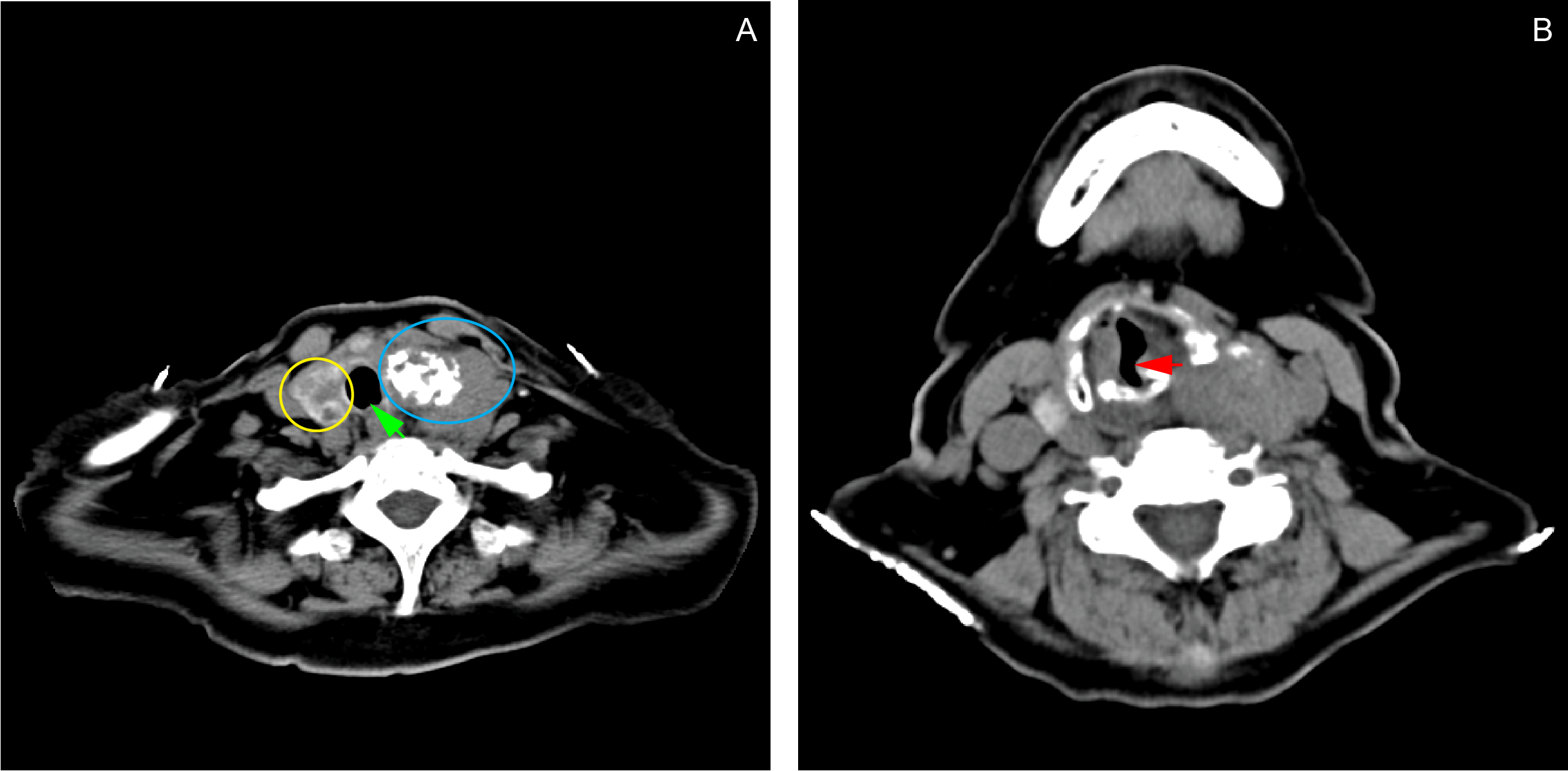

The patient also had a 4-year history of palpable anterior neck mass with no associated symptoms. Two years after the onset of the neck mass, the patient started to have voice hoarseness, which prompted her to seek consultation at our institution’s ENT Department. A contrast neck CT scan done revealed a probably malignant left thyroid mass, multiple thyroid cysts on the right lobe, and a calcified mediastinal node. The results of the FNAB done two years before admission revealed that the mass was a colloid nodular goiter. She was prescribed levothyroxine 25 mcg daily, which she took with good compliance. The patient was advised thyroidectomy, but she refused to go through the procedure. A contrast chest CT scan done prior to this admission showed that the thyroid mass now extended to the trachea, causing a partial airway obstruction. (Figure 2)

The patient had been hypertensive for more than 10 years and had been taking losartan 100 mg daily, with good compliance to treatment. She was diagnosed to have bronchial asthma four years prior to admission and had been taking salbutamol nebulizations as needed during asthma exacerbations. She didn’t smoke cigarettes nor drink alcoholic beverages, and she had no family history of cancer.

The patient mainly consented to be admitted because of the bleeding from the anal mass, but she agreed to submit to further work up for both the anal mass and the anterior neck mass upon admission. On physical examination during admission, the patient was awake, coherent, and not in mild respiratory distress. No cervical, clavicular and axillary lymphadenopathies could be palpated. There was a 3 x 3 x 1 cm firm, non-tender anterolateral neck mass, which moves with deglutition. (Figure 3) Breath sounds were clear. The abdomen was soft, non-tender, without any palpable mass. However, there was a palpable right inguinal mass, which was firm and fixed, measuring 5 x 4 x 4 cm in size, with no associated skin discoloration. There was good anal sphincter tone on digital rectal examination. A black, pedunculated mass, measuring 6 x 7 x 6 cm in size, and attached to the right anal margin could be observed. (Figure 4)

On admission, the ENT service assessed the patient as having an impending airway compromise secondary to a probably malignant multinodular goiter, and a paralyzed left vocal cord. Prophylactic tracheostomy was suggested to relieve the patient’s dyspnea. The thyroid panel results showed normal TSH (2.06 mIU/L), normal total T4 (109.67 nmol/L), and slightly decreased total T3 (0.94 nmol/L) levels. The chest radiograph showed unremarkable pulmonary findings and a calcified left cervical mass, which points to the thyroid mass previously mentioned. The General Surgery service performed a FNAB of the anterior neck mass, and the cytologic features of the aspirate were consistent with the Category V Bethesda Classification, suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma. A total thyroidectomy was again advised, but the patient refused. As a result, no further plans were pursued for the anterior neck mass and we proceeded with the management of the patient’s anal mass.

Hemoglobin count on admission showed anemia (83 g/L), hence, the patient was transfused with 3 units of packed RBC prior to her contemplated surgery. An endorectal ultrasound done during admission revealed the presence of a 4.6 x 3.8 mm perirectal lymph node in the posterolateral aspect, making the tumor a stage II anal melanoma.

At this point, the therapeutic plan was to do a wide excision of the anal mass and an excision biopsy of the palpable right inguinal mass. The patient was placed in lithotomy position and the anal mass was retracted laterally to expose its base on the anal canal. On digital rectal examination, the fungating mass was noted at the right posterolateral position of the anus, involving the anal sphincter. An incision was made around the base of the mass, approximately 1-2 cm deep into the puborectalis muscle. The mass was excised entirely, with grossly no visible part of the mass left on the surgical site. A 3-cm transverse incision was made over the right inguinal area above the palpable inguinal mass. Blunt dissection was done to remove the clumped inguinal lymph nodes. We sent both the anal mass and the inguinal mass for histopathologic examination.

Grossly, the excised anal lesion showed a tan to red polypoid mass, measuring 5 x 4 x 3 cm in size, (Figure 5) while the inguinal lesion showed three lymph nodes, each measuring 0.6 cm in diameter. Histological examination showed solid and diffuse atypical cells invading the surrounding fibrous stroma. The individual cells exhibit round to oval, deeply basophilic nuclei and abundant clear eosinophilic cytoplasm. All margins of resection as well as the three dissected lymph nodes isolated from the right inguinal region were positive for tumor cells. The histological findings confirmed the diagnosis of anal malignant melanoma, with right inguinal lymph node metastasis.

Our final diagnoses on the patient’s conditions upon discharge were: anal melanoma, Stage IIIB (T3N3M0); and, papillary thyroid carcinoma, Stage III (T4aN1M0).

The patient had an unremarkable course postoperatively and was discharged four days after the excision of the anal mass. Ten days after the surgery, we noted good healing in the surgical site with no bleeding. A month after the surgery, the patient reported to have been able to sit, defecate, and perform other activities of daily living without difficulty. Four months after the surgery, the patient reported minimal bleeding near the surgical site, and we noted another hyperpigmented nodular lesion measuring 1 x 1 cm in size on the anal verge. The patient did not report any symptoms referable to the anterior neck mass, but she pointed out a new-onset, 2 x 2- cm, palpable, firm, and movable breast mass located at the upper inner quadrant of her right breast. We could not palpate any axillary or clavicular nodes on examination. We apprised the patient of the poor prognosis of her recurrent anal mass and the possibility of having more metastases to the other parts of her body. We also told her about the possibility of a second excision procedure in the near future if intractable bleeding from the new-onset anal mass ensues. She was then lost to follow up. Six months after her last follow up, her family informed us about her death at home.

|

|

Figure 1

Coronal (A, C) and axial (B) views of contrast CT scan of the whole abdomen. A fairly-defined, heterogeneously-enhancing, fungating mass, measuring 5.40 x 3.14 x 5.81 cm, is seen in the anal region, infiltrating the puborectalis muscle, anal sphincter and perineal muscles (A: yellow ring). A second, well-defined, lobulated, enhancing, hypodense mass measuring 5.29 x 4.58 x 4.33 cm is also noted at the right inguinal area (B, C: red ring).

A 6 x 7 x 6 cm black, fungating, pedunculated, non-tender mass located within the anal orifice.

|

|

|

Figure 2

Contrast chest CT scan showing a fairly-defined, heterogeneously-enhancing lesion (4.41 x 5.31 x 3.89 cm) with internal coarse calcifications seen in the left thyroid lobe (A: blue ring). Soft tissue extension from the thyroid gland into the trachea causes narrowing of the airway at the level of T1 (B: red arrow). The mass also deviates the trachea to the right (A: green arrow). The right thyroid lobe contains multiple subcentimeter, hypodense, non-enhancing, non-calcified lesions (A: yellow ring).

|

|

|

Figure 3

A 3 x 3 cm firm, anterior neck mass that moves with deglutition.

|

|

|

Figure 4

A 6 x 7 x 6 cm black, fungating, pedunculated, non-tender mass located within the anal orifice.

|

|

|

Figure 5

Postoperative view of the patient’s anal orifice after excision of the anal and inguinal masses, with exposure of the base of the pedunculated anal mass at posterolateral right aspect of the anal canal.

|

|

|

Figure 6

Gross image of the anal lesion after excision. The fleshy black polypoid mass measures 5 x 4 x 3 cm.

|

References

1. Khan M, Bucher N, Elhassan A, Barbaryan A, Ali AM, Hussain N, Mirrakhimov AE. Primary anorectal melanoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2014 Mar 13;7(1):164-70.

2. Singer M, Mutch MG. Anal melanoma. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2006 May;19(2):78-87.

3. Tacastacas JD, Bray J, Cohen YK, Arbesman J, Kim J, Koon HB, Honda K. et al. Update on primary mucosal melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):366–375.

4. Jehangir W, Schlacter N, Singh S, Enakuaa S, Islam MA, Sen S, Yousif A. Anorectal Melanoma: A Case Report and an Update of a Rare Malignancy. World J Oncol. 2015 Feb;6(1):308-310.

5. Malaguarnera G, Madeddu R, Catania VE, Bertino G, Morelli L, Perrotta RE, et al. Anorectal mucosal melanoma. Oncotarget. 2018 Jan 2;9(9):8785-8800.

6. Mahmood MN, Lee MW, Linden MD, Nathanson SD, Hornyak TJ, Zarbo RJ. Diagnostic value of HMB-45 and anti-Melan A staining of sentinel lymph nodes with isolated positive cells. Mod Pathol. 2002 Dec;15(12):1288-93.

7. Wang S, Sun S, Liu X, Ge N, Wang G, Guo J, Liu W, Wang S. Endoscopic diagnosis of primary anorectal melanoma. Oncotarget. 2017 Jul 25;8(30):50133-50140.

8. McBrearty A, Porter D, McCallion K. Anal Melanoma: A General Surgical Experience. J Clin Case Rep. 2015;5:2.

9. Kothonidis K, Maassarani F, Couvreur Y, Vanhoute B, De Keuleneer R. Primary anorectal melanoma-a rare entity: case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2017 Mar 29;2017(3):rjx060.

10. Tomioka K, Ojima H, Sohda M, Tanabe A, Fukai Y, Sano A, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the rectum: report of two cases. Case Rep Surg. 2012;2012:247348.

11. Veloso ADC, Magno JCC, Silva JADDC. Anal melanoma: a rare,but catastrophic tumor. J Coloproctol. (Rio J.) [Internet]. 2014 Mar [cited 2020 Sep 20]; 34(1):9-13. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2237-93632014000100009.

12. Limaiem F, Rehman A, Mazzoni T. Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. [Updated 2020 Oct 16]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536943/.

13. Dean DS, Gharib H. Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy of the Thyroid Gland. [Updated 2015 Apr 26]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285544/.

14. Zhang C, Yanshuang L, Jiyu L, Chen,X. Total thyroidectomy versus lobectomy for papillary thyroid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine; 2020 February:99(6)pe19073.

15. Shah JP. Thyroid carcinoma: epidemiology, histology, and diagnosis. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2015 Apr;13(4 Suppl 4):3-6.

16. Albi E, Cataldi S, Lazzarini A, Codini M, Beccari T, Ambesi-Impiombato FS, Curcio F. Radiation and Thyroid Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Apr 26;18(5):911.

17. Somasundar PS. Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Workup. 2018 Jun 18 [cited 2020 Dec 30]. In: Medscape [Internet]. New York: Medscape. C1994-2020. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/282276-workup.

18. Song E, Han M, Oh HS, Kim WW, Jeon MJ, Lee YM, Kim TY, Chung KW, Kim WB, Shong YK, Hong SJ, Sung TY, Kim WG. Lobectomy Is Feasible for 1-4 cm Papillary Thyroid Carcinomas: A 10-Year Propensity Score Matched-Pair Analysis on Recurrence. Thyroid. 2019 Jan;29(1):64-70.

19. Haugen BR. Radioiodine remnant ablation: current indications and dosing regimens. Endocr Pract. 2012 Jul-Aug;18(4):604-10.

20. Tang J, Kong D, Cui Q, Wang K, Zhang D, Liao X, Gong Y, Wu G. The role of radioactive iodine therapy in papillary thyroid cancer: an observational study based on SEER. Onco Targets Ther. 2018 Jun 19;11:3551-3560.

21. Johnson CH. SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual 2004, Revision 1. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2004. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/manuals/2004Revision1/SPM_2004_maindoc.r1.pdf.

22. Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin L, Parkin DM, et al, editors. Internal classification of diseases for oncology (ICD-O). 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

23. Hassan MA, Fakhrudiin N, Farhat F. Synchronous invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast and clear cell renal carcinoma with rare presentation and behaviour: a case report with a literature review. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020 Oct 8;14:1120.

24. Vogt A, Schmid S, Heinimann K, Frick H, Herrmann C, Cerny T, Omlin A. Multiple primary tumours: challenges and approaches, a review. ESMO Open. 2017 May 2;2(2):e000172.

25. Sandeep TC, Strachan MW, Reynolds RM, Brewster DH, Scélo G, Pukkala E, et al. Second primary cancers in thyroid cancer patients: a multinational record linkage study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 May;91(5):1819-25.

26. Zubaidi A. Multiple primary cancers of the colon, rectum, and the thyroid gland. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008 Oct;14(4):202-5.

27. Skelton WP 4th, Ali A, Skelton MN, Federico R, Bosse R, Nguyen TC, et al. Analysis of Overall Survival in Patients With Multiple Primary Malignancies: A Single-center Experience. Cureus. 2019 Apr 27;11(4):e4552.

Copyright © 2020 SMB Santos, et al.