Health care approach to burn mass casualty incidents: policy notes

SPMC J Health Care Serv. 2024;10(1):5 ARK: https://n2t.net/ark:/76951/jhcs2g3q4f

1Department of Emergency Medicine, Southern Philippines Medical Center, JP Laurel Avenue, Bajada, Davao City

2Research Utilization and Publication Unit, Southern Philippines Medical Center, JP Laurel Ave, Davao City, Philippines

Correspondence Benedict Edward P Valdez, rbenz628@gmail.com

Received 15 March 2024

Accepted 5 June 2024

Cite as Valdez BEP, Paderanga MAR, David JDM, Perandos-Astudillo CM, Roño RC. Health care approach to burn mass casualty incidents: policy notes. SPMC J Health Care Serv. 2024;10(1):5. https://n2t.net/ark:/76951/jhcs2g3q4f

Introduction

Main evidence

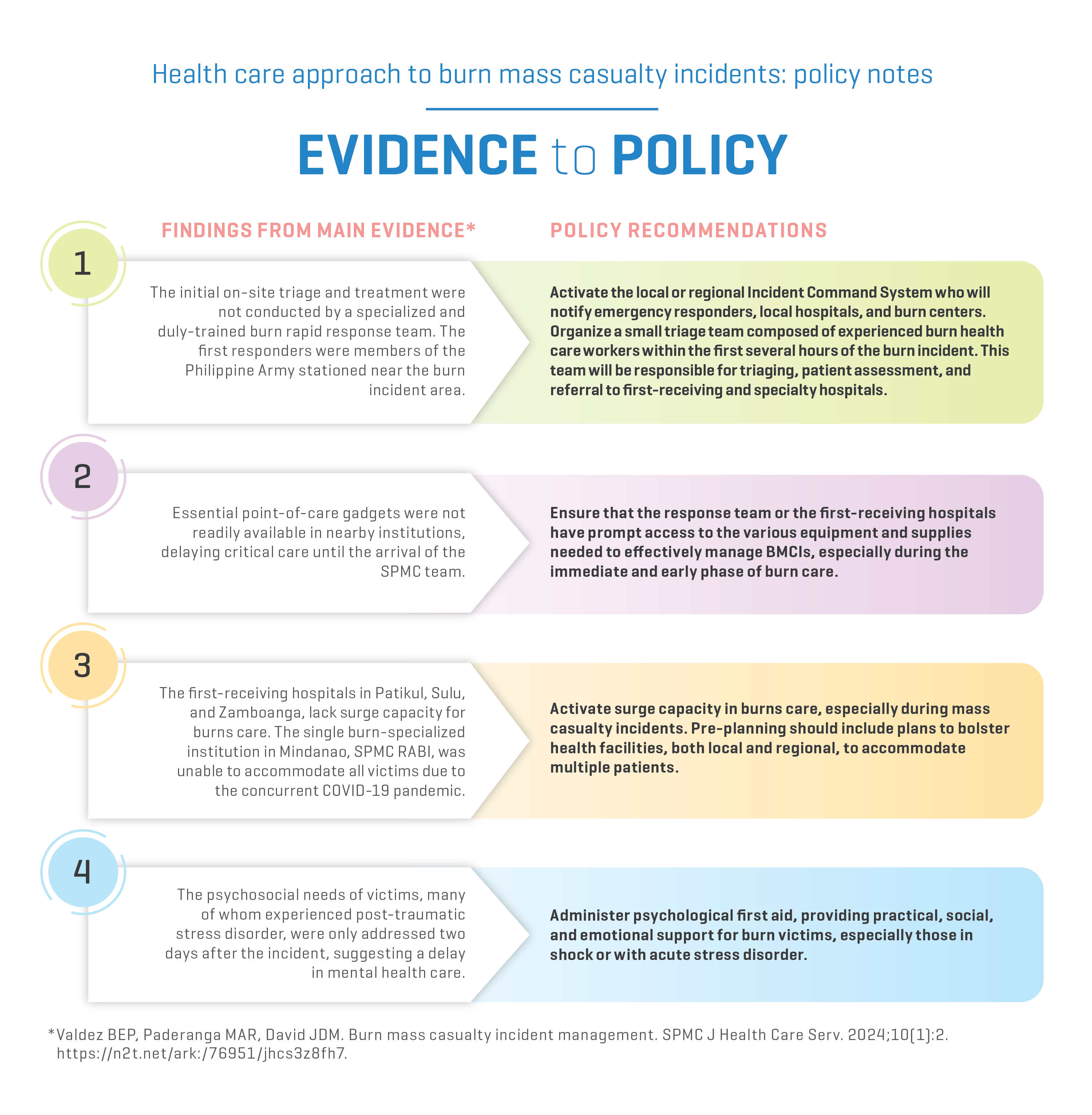

Evidence-to-policy diagram

Related evidence

Contributors

BEPV, MARP, JDMD, CMPA and RCR contributed to the conceptualization of this article. All authors wrote the original draft, performed the subsequent revisions, approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of this report.

Article source

Commissioned

Peer review

Internal

Competing interests

None declared

Access and license

This is an Open Access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which allows others to share and adapt the work, provided that derivative works bear appropriate citation to this original work and are not used for commercial purposes. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

References

1 Gauglitz GG. Overview of the management of the severely burned patient. 2023 Nov 15 [cited 2024 Jun 18]. In: UpToDate [Internet]. Illinois: UpToDate, Inc. c2024. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-management-of-the-severely-burned-patient/print.

2 Hughes A, Almeland SK, Leclerc T, Ogura T, Hayashi M, Mills JA, et al. Recommendations for burns care in mass casualty incidents: WHO Emergency Medical Teams Technical Working Group on Burns (WHO TWGB) 2017-2020. Burns. 2021 Mar;47(2):349-370.

3 Kearns RD, Marcozzi DE, Barry N, Rubinson L, Hultman CS, Rich PB. Disaster Preparedness and Response for the Burn Mass Casualty Incident in the Twenty-first Century. Clin Plast Surg. 2017 Jul;44(3):441-449.

4 Department of Health Philippines. MANUAL OF OPERATIONS on Health Emergency and Disaster Response Management. 2015. Available from: https://hospitalsafetypromotionanddisasterpreparedness.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/complete-manual-20150129.pdf

5 Valdez BEP, Paderanga MAR, David JDM. Burn mass casualty incident management. SPMC J Health Care Serv. 2024;10(1):2. https://n2t.net/ark:/76951/jhcs3z8fh7

6 Ahuja RB, Bhattacharya S. Burns in the developing world and burn disasters. BMJ. 2004 Aug 21;329(7463):447-9.

7 Kearns RD, Conlon KM, Valenta AL, Lord GC, Cairns CB, Holmes JH, et al. Disaster planning: The basics of creating a burn mass casualty disaster plan for a burn center. Journal of Burn Care & Research. 2014 Jan 1;35(1):e1-e13.

8 National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. Implementing guidelines on the use of Incident Command System (ICS) as on-scene disaster response and management mechanism under Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management System (PDRRMS), Memorandum Circular No. 04 Series 2012, 2012 Mar 28.

9 Crossett JR, Peterson WC, King BT. Burn mass casualty disaster. Medical Research Archives. 2018;6(8).

10 Restrata. Incident command system for more effective crisis management. Available from: https://www.restrata.com/blog/incident-command-system-for-more-effective-crisis-management/

11 Lyall A, Bhadauria AS. Fluid management in major burns. 2024 [cited 2024 Jun 18]. In: Malbrain ML, Wong A, Nasa P, Ghosh S, editors. Rational use of intravenous fluids in critically ill patients. New York: Springer. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-42205-8_19.

12 Hudspith J, Rayatt S. First aid and treatment of minor burns. BMJ. 2004 Jun 19;328(7454):1487-9.

13 Streitz MJ. How to do burn escharotomy. 2023 Apr [cited 2024 Jun 18]. In: MSD Manual Professional Version [Internet]. New Jerser: Merck & Co., Inc. c2024. Available from: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/how-to-do-skin,-soft-tissue,-and-minor-surgical-procedures/how-to-do-burn-escharotomy.

14 Hayashi K, Sasabuchi Y, Matsui H, Nakajima M, Otawara M, Ohbe H, et al. Does early excision or skin grafting of severe burns improve prognosis? A retrospective cohort study. Burns. 2023 May;49(3):554-561.

15 Goswami P, Sahu S, Singodia P, Kumar M, Tudu T, Kumar A, et al. Early Excision and Grafting in Burns: An Experience in a Tertiary Care Industrial Hospital of Eastern India. Indian J Plast Surg. 2019 Sep;52(3):337-342.

16 Procter F. Rehabilitation of the burn patient. Indian J Plast Surg. 2010 Sep;43(Suppl):S101-13.

17 Fetter JC. Psychosocial Response to Mass Casualty Terrorism: Guidelines for Physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(2):49-52.

18 European Federation of Psychologists Associations. Lessons learned in psychosocial care after disasters. Council of Europe. 2010 Jul. Available from: https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/majorhazards/ressources/pub/Lessonslearned_Oct2010_EN.pdf.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License that allows others to share the work for non-commercial purposes with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional, non-commercial contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors grant the journal permission to rewrite, edit, modify, store and/or publish the submission in any medium or format a version or abstract forming part thereof, all associated supplemental materials, and subsequent errata, if necessary, in a publicly available publication or database.

- Authors warrant that the submission is original with the authors and does not infringe or transfer any copyright or violate any other right of any third parties.