Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae panophthalmitis with perinephric and psoas abscesses in a 42-year-old female: case in images

SPMC J Health Care Serv. 2020;6(1):8 ARK: https://n2t.net/ark:/76951/jhcs39brs9

1Department of Ophthalmology, Southern Philippines Medical Center, JP Laurel Ave, Davao City, Philippines

Correspondence Charmaine Grace P Malabanan-Cabebe, charmainegrace.0923@gmail.com

Received 2 March 2020

Accepted 29 June 2020

Cite as Malabanan-Cabebe CGP, Villano MAF. Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae panophthalmitis with perinephric and psoas abscesses in a 42-year-old female: case in images. SPMC J Health Care Serv. 2020;6(1):8. https://n2t.net/ark:/76951/jhcs39brs9

|

|

Figure 2 Anterior segment photo showing diffuse conjunctival injection and extensive fibrin formation in the right eye. |

|

|

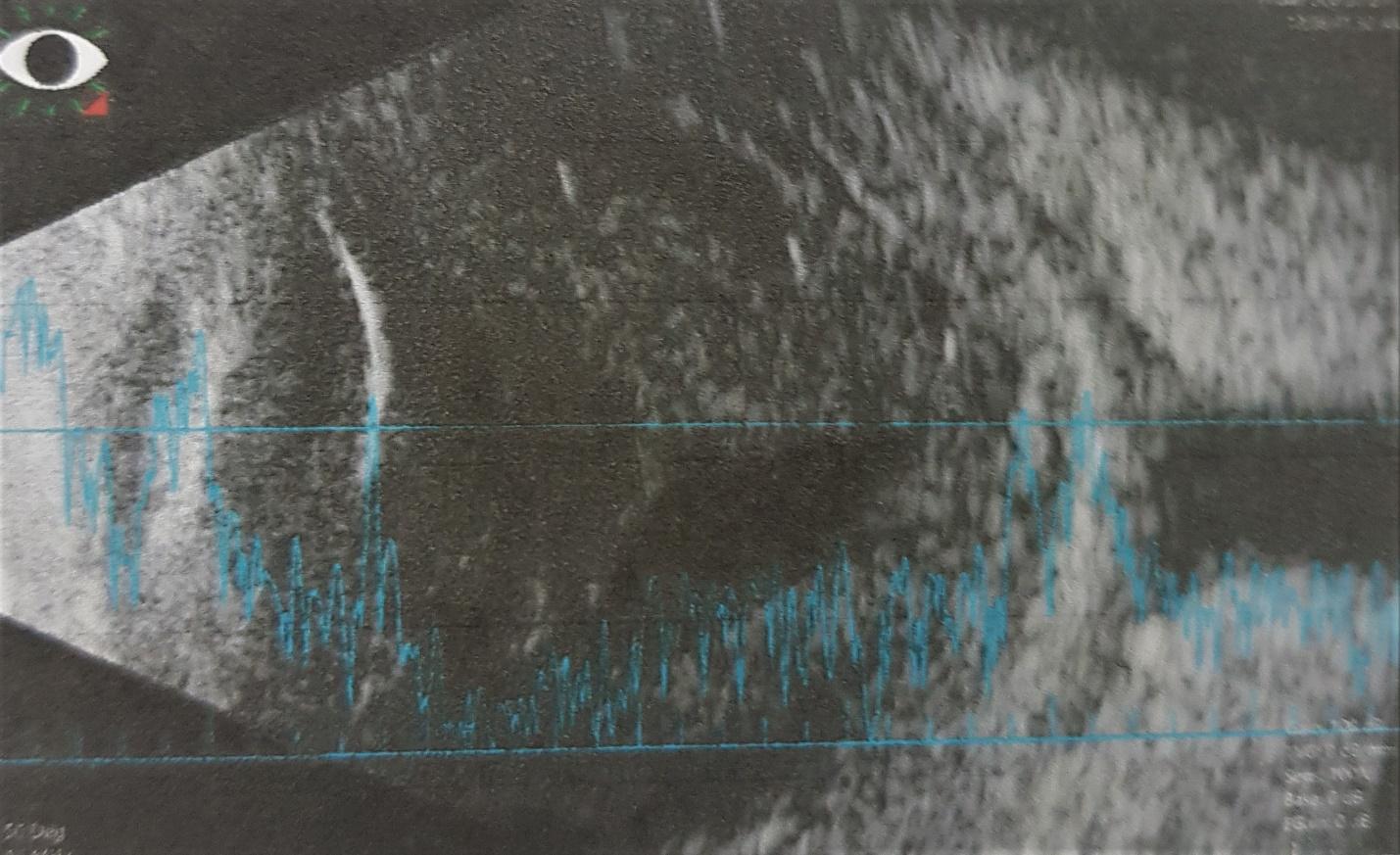

Figure 3 B-scan of the right eye, revealing mild- to moderate-amplitude point echoes with choroidal thickening. |

|

|

Figure 4 Coronal (A) and axial (B) views of contrast CT scan of the whole abdomen, done on the 21st hospital day, showing left perinephric and psoas abscesses. |

|

|

Figure 5 Anterior segment photo of the right eye showing marked decrease in anterior chamber inflammation with 360o posterior synechiae. |

Patient consent

Obtained

Reporting guideline used

Article source

Submitted

Peer review

External

Competing interests

None declared

Access and license

This is an Open Access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which allows others to share and adapt the work, provided that derivative works bear appropriate citation to this original work and are not used for commercial purposes. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

References

1. Egan, DJ. Endophthalmitis. 2018 Jul 2 [cited 2020 Jun 29]. In: Medscape. New York: Medscape. C1994-2020. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/799431-overview#a6

2. Sheu SJ. Endophthalmitis. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2017 Aug;31(4):283-289. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2017.0036. Epub 2017 Jun 28.

3. Chen KJ, Chen YP, Chao AN, Wang NK, Wu WC, Lai CC, Chen TL. Prevention of evisceration or enucleation in endogenous bacterial panophthalmitis with no light perception and scleral abscess. 2017 PLoS ONE, 12 (1) , art. no. 0169603.

4. Chaudhry IA, Al-Dhibi H, Al-Rashed W, Al- Mezaine HS, Arat YO, Abdelghani W. Endophthalmitis: Experience from a Tertiary Eye Care Center, Common Eye Infections, Imtiaz A. Chaudhry, (May 8th 2013). IntechOpen, DOI: 10.5772/54431. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/common-eye-infections/endophthalmitis-experience-from-a-tertiary-eye-care-center.

5. Durand ML. Bacterial and Fungal Endophthalmitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017 Jul;30(3):597-613. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00113-16.

6. Sadiq MA, Hassan M, Agarwal A, Sarwar S, Toufeeq S, Soliman MK, Hanout M, Sepah YJ, Do DV, Nguyen QD. Endogenous endophthalmitis: diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2015 Dec;5(1):32.

7. Yuan, Z, Liang X, Zhong, J. The disease course of bilateral endogenous fungal endophthalmitis. J Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;8(1):639.

8. Kashani AH, Eliott D. The emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae endogenous endophthalmitis in the USA: basic and clinical advances. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3(1):28. Published 2013 Feb 4.

9. Sridhar J, Flynn HW Jr, Kuriyan AE, Dubovy S, Miller D. Endophthalmitis caused by Klebsiella species. Retina. 2014 Sep;34(9):1875-81.

10. Sheu SJ, Kung YH, Wu TT, Chang FP, Horng YH. Risk factors for endogenous endophthalmitis secondary to klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: 20-year experience in Southern Taiwan. Retina. 2011 Nov;31(10):2026-31.

11. Kernt M, Kampik A. Endophthalmitis: Pathogenesis, clinical presentation, management, and perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010 Mar 24;4:121-35.

12. Davis JL. Diagnostic dilemmas in retinitis and endophthalmitis. Eye (Lond). 2012 Feb;26(2):194-201. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.299. Epub 2011 Nov 25.

13. Behlau I. Endophthalmitis. Infectious Disease Advisor [Internet]. c2020 [cited 2020 June 30]. Available from: https://www.infectiousdiseaseadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/infectious-diseases/endophthalmitis/.

14. Birnbaum, F, Gupta, G. Endogenous endophthalmitis: Diagnosis and treatment. 2016 Jun [cited 2020 June 30]. In: American Academy of Ophthalmology. California: American Academy of Ophthalmology. C2020. Available from: https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/endogenous-endophthalmitis-diagnosis-treatment.

15. Zhang YQ, Wang WJ. Treatment outcomes after pars plana vitrectomy for endogenous endophthalmitis. Retina. 2005 Sep;25(6):746-50.

16. Vaziri K, Schwartz SG, Kishor K, Flynn HW Jr. Endophthalmitis: state of the art. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015 Jan 8;9:95-108.

17. Yonekawa Y, Chan RP, Reddy AK, Pieroni CG, Lee TC, & Lee S. Early intravitreal treatment of endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 2011 39(8), 771–778.

18. Peyman GA, Raichand M, Bennett TO. Management of endophthalmitis with pars plana vitrectomy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980 Jul;64(7):472-5.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License that allows others to share the work for non-commercial purposes with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are able to enter into separate, additional, non-commercial contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors grant the journal permission to rewrite, edit, modify, store and/or publish the submission in any medium or format a version or abstract forming part thereof, all associated supplemental materials, and subsequent errata, if necessary, in a publicly available publication or database.

- Authors warrant that the submission is original with the authors and does not infringe or transfer any copyright or violate any other right of any third parties.